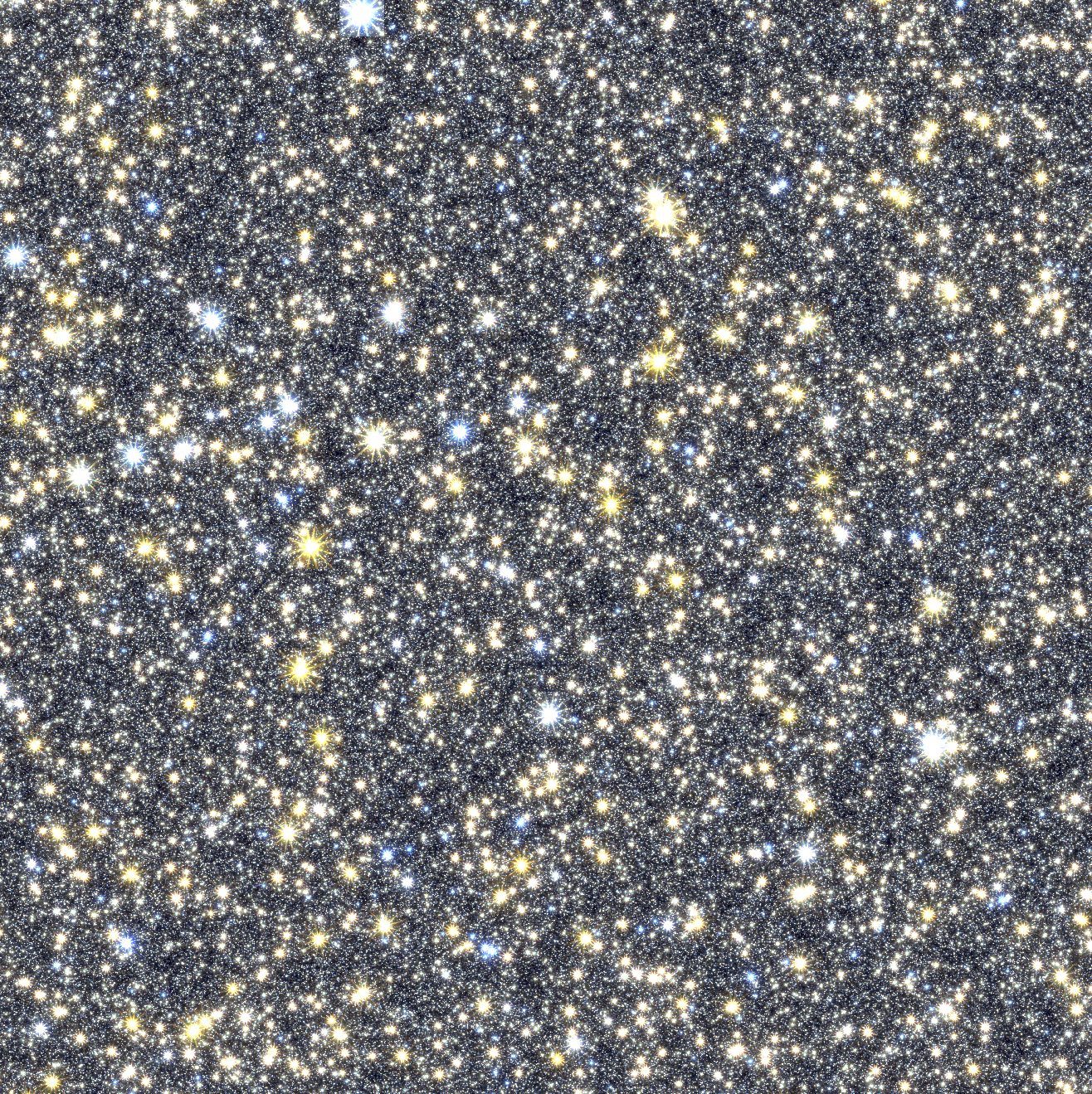

At the heart of our own galaxy, there is a dense thicket of stars with a supermassive black hole at the very center. NASA’s Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope will provide the deepest-ever view of this zone, revealing stars, planets, and unique objects that resist definition.

Based on the input of astronomers from across the globe, the Roman Space Telescope will spend three-quarters of its five-year primary mission conducting three revolutionary surveys of unprecedented scale. Their combined results will transform all areas of astronomy and answer longstanding questions about dark matter, dark energy, and planets outside of our solar system, called exoplanets.

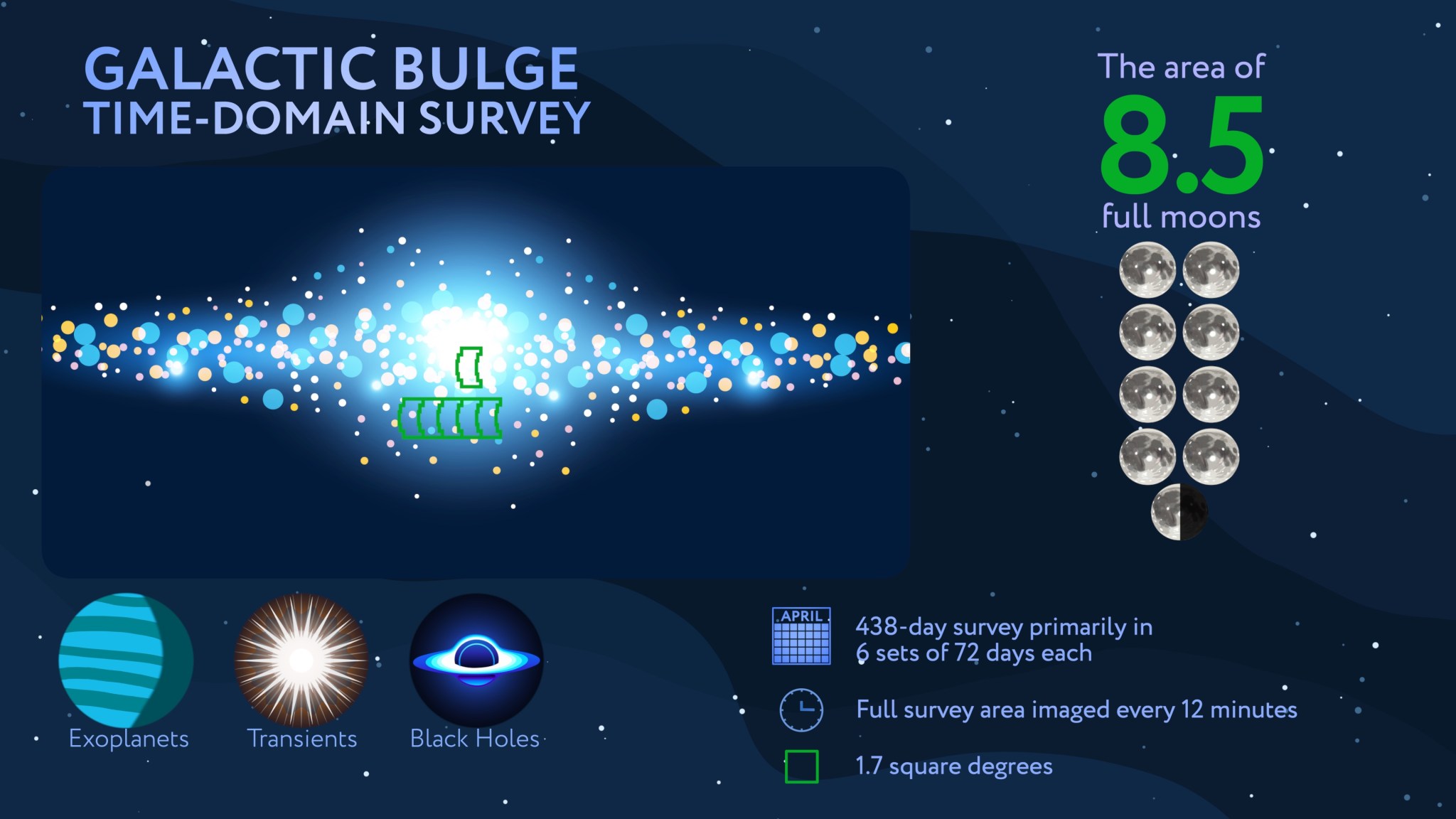

That last theme will be addressed by the Galactic Bulge Time-Domain Survey, which will peer into the center of our galaxy to study the stars and exoplanets that make up the densely populated region around the center of the Milky Way, known as the galactic bulge.

The survey will observe six patches of the galactic bulge, one pinpointing the center and five nearby, every 12 minutes during 438 days of total observing time. The observations will be separated into six “seasons” spread out over five years.

Spending so much time focusing on a relatively small area of the sky, the mission will be able to track changes in the motion and light of hundreds of millions of stars, and any planets that orbit them, over long periods — the “time-domain” aspect of the survey.

“This survey will be the highest precision, highest cadence, longest continuous observing baseline survey of our galactic bulge, where the highest density of stars in our galaxy reside,” said Jessie Christiansen of Caltech/IPAC, who served as co-chair of the committee that defined the Galactic Bulge Time-Domain Survey.

Exoplanet microlensing

Roman will use a method called microlensing to search for exoplanets, a technique that has so far identified just over 200 exoplanets, compared to more than 4,000 discovered with the transit method, out of the greater than 6,000 currently confirmed.

With this survey, scientists expect to see over 1,000 new planets orbiting other stars just using microlensing alone. This would increase the number of exoplanets identified using this method by more than fivefold.

A microlensing event is when light from a distant star in the background is warped slightly by a foreground object, like a star and its planet. This warping of light is called gravitational lensing, with the gravity from the star and planet bending the fabric of space that light is traveling through and focusing it like a magnifying glass.

Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center/CI Lab

While the transit method is very good at identifying exoplanets that orbit close to their star, the microlensing method can discover exoplanets that orbit farther away from their star, and in planetary systems farther from Earth than ever studied before. Roman will be versatile enough to see exoplanets dwelling from the inner edge of the habitable zone out to great distances from their stars, with a wide range of masses from planets smaller than Mars to the size of gas giants like Jupiter and Saturn. It may even discover “rogue planets” without host stars that either formed alone or were ejected from their host systems long ago.

“For the first time, we will have a big picture understanding of Earth and our solar system within the broader context of the exoplanet population of the Milky Way galaxy,” Christiansen said. “We still don’t know how common Earth-like planets are, and the Roman Galactic Bulge Time-Domain Survey will provide us with this answer.”

This survey will create a census of exoplanets for scientists to draw statistical conclusions from, revealing common patterns found in exoplanets and furthering our understanding of planetary formation and habitability.

One survey; lots of science

Because of the immense amount of observing time and subsequent data produced, the Galactic Bulge Time-Domain Survey will advance not only the field of exoplanet microlensing, but other areas of astronomy, too.

“There is an incredibly rich diversity of science that can be done with a high-precision, high-cadence survey like this one,” said Dan Huber of the University of Hawaii, the other survey co-chair.

The core survey was optimized not only for microlensing, but also to observe changes in brightness from small, fast blips to long-term trends. This property allows astronomers to discover and characterize transiting planets, red giant stars, stellar-mass black holes and other stellar remnants, and eclipsing binaries, and can lead to a deeper understanding about the physics of star formation and evolution.

“The stars in the bulge and center of our galaxy are unique and not yet well understood,” Huber said. “The data from this survey will allow us to measure how old these stars are and how they fit into the formation history of our Milky Way galaxy.”

Roman’s observing strategy in the Galactic Bulge Time-Domain Survey, as well as the High-Latitude Time-Domain Survey and the High-Latitude Wide-Area Survey, will allow astronomers to maximize scientific output, all with one telescope.

Abundance of data to explore

Roman will observe hundreds of millions of stars every 12 minutes during the survey period, providing an unprecedented volume of data for astronomers to parse through.

The Roman Science Support Center at Caltech/IPAC in Pasadena, California, will be responsible for the high-level science data processing for the Galactic Bulge Time Domain Survey, including exoplanet microlensing and general community outreach for Roman exoplanet science. The Science Support Center’s monitoring of these stars has been automated to detect microlensing and variable events within the data. This helps scientists understand features like how frequently a star’s brightness is changing, or if there are planets lurking near the lensed stars, or other sources of variability. The number of stars and frequency of the observations make the Roman data an ideal dataset for finding such sources.

All Roman observations will be made publicly available after a short processing period. The mission is scheduled to launch no later than May 2027, with the team on track for launch in fall 2026.

The Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope is managed at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, with participation by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California; Caltech/IPAC in Pasadena, California; the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore; and a science team comprising scientists from various research institutions. The primary industrial partners are BAE Systems Inc. in Boulder, Colorado; L3Harris Technologies in Rochester, New York; and Teledyne Scientific & Imaging in Thousand Oaks, California.

By Isabel Swafford

Caltech/IPAC, Pasadena, Calif.

Media contact:

Claire Andreoli

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.

301-286-1940