19 min read

A Tapestry of Tales: 10th Anniversary Reflections from NASA’s OCO-2 Mission

When woven together, the tapestry of experiences of staff and scientists provide the complete picture of OCO-2.

Breathe in… Breathe out.

This simple rhythm sets the foundation of life on Earth – and it’s a pattern that a NASA satellite has been watching from space for over a decade.

On July 2, 2024, NASA’s Orbiting Carbon Observatory-2 (OCO-2) celebrated 10 years since its launch. Built by NASA/Jet Propulsion Laboratory (NASA/JPL), OCO-2 is now viewed as the gold standard for carbon dioxide (CO2) measurements from space and has quietly become a powerful driver of technological, ecological and even economic progress – including providing unexpected insights into plant health, crop-yield forecasting, drought early warning systems, and forest and rangeland management.

While the mission can point to many scientific achievements – some of which will be highlighted in the pages that follow – these accomplishments have occurred in the context of a larger human story. Scientists from around the world have come together to bring the important data from this satellite to the broader community, making OCO-2 the success that it is today.

This article provides readers an introduction to several transformative characters in this carbon story. The text peers behind the scenes to reveal the circuitous path that scientists and engineers must navigate to take a brilliant scientific concept and turn it into flight hardware that can be launched into space to make beneficial observations. The article depicts milestones that mark the mission’s successes, but also the failures, dead ends, long nights, and discouragements that make up the complexity of any science story.

2003: The First OCO Science Team Meeting

Measuring CO2 from space: Great idea but can it really be done?

When the idea for OCO was first proposed, it wasn’t universally embraced. At the time, more than a few experts scoffed at the idea that CO2 could be measured from space. Unlike nitrogen and oxygen, which are the dominant components of Earth’s atmosphere, CO2 is a trace gas, often no more than a few hundred parts per million. Miniscule, elusive, and nomadic, these measurements, though challenging, are crucial because of the important role CO2 plays in global climate.

In April 2003, a handful of hopeful scientists gathered at the California Institute for Technology (Caltech) for the first OCO Science Team meeting. To mark the occasion, they took a break during the meetings and lined up for a group photo – see Photo 1. Upon returning to work, they took up the arduous task of determining how to measure CO2 from space with a satellite and instrument hardware that simply did not exist.

OCO-2 was developed as part of NASA’s Earth System Science Pathfinder program, which supports small, low-cost missions that can still provide tremendous value for high-impact goals. The satellite carries a high-resolution spectrometer that collects data in three, narrow spectral bands. These spectral bands follow a divide and conquer strategy – two measure the clear “fingerprint” that CO2 leaves when it absorbs sunlight, and one takes the same measurement for oxygen (O2). The satellite is able to estimate CO2 concentrations by comparing the CO2 and O2 measurements.

2014: A Night at Vandenberg Air Force Base – To Launch or Not to Launch

A Mother and daughter await the midnight launch.

On a warm July evening in 2014, Vivienne Payne [JPL—current OCO-2 Project Scientist] would normally have tucked her four-year-old daughter into bed. But this night was special. They were lined up in a crowd waiting for a bus to take them to Vandenberg Air Force Base (now Space Force Base) in California. The group huddled in the chill night air awaiting the launch of the OCO satellite into the cosmos.

Shortly after midnight, hundreds of guests spread blankets across the gravelly ground to make their wait more comfortable. The air was charged with excitement. The participants waited quietly, murmuring to one another while the soft slosh of the Pacific Ocean offered a steady pendulum counting down to the impending launch. Like most people there that night, Vivienne felt upbeat and excited, but she also understood the gravity of the moment – a lot was riding on this launch.

While Vivienne had not been part of OCO since inception – having joined the project in 2012 – she knew OCO’s story. The first launch in 2009 ended in failure – when a faulty launch vehicle doomed the first OCO to a watery grave just moments after launch. In the aftermath, the OCO community were left in limbo, unsure if the project would survive. All was not lost. The Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) had successfully launched the Greenhouse-gas Observing satellite (GOSAT or IBUKI, Japanese for “breath”) that same year. This launch gave the OCO team an opportunity to test and refine their methods and algorithms using data from GOSAT.

As the gravel poked through the thick flannel blankets, Vivienne shifted uncomfortably waiting for the interminable countdown to reach its conclusion – and then everything stopped. A technical issue was detected, triggering a command to abort the launch.

Vivienne tried to explain to her disappointed daughter that this was simply how things went with space work. Sometimes you put in 1000 work-years of labor, get up in the middle of the night, and sit on uneven ground just to have everything stopped, unceremoniously.

Fortunately, the problem was quickly resolved, and the launch was rescheduled for the very next night. The participants returned to the staging site – rinse and repeat. This time Vivienne’s daughter was decidedly more sluggish. At 3:00 AM PDT, OCO-2 launched flawlessly into space. Unfortunately, a layer of fog obscured the spectators’ view. While it could not be seen, the resounding boom of the rocket taking off could be heard for miles.

For Vivienne, the sonic boom shocked the ears and rumbled through the bodies of the assembled crowd, who erupted in cheers. Having invested a lot of her time in the OCO project during the past two years, she was thrilled to see a successful launch.

As they returned to their hotel, Vivienne’s daughter remained unimpressed. “Mummy, let’s not do that again,” she said as she splayed out on the hotel bed and soon fell fast asleep.

2014: OCO-2 Joins A Larger Earth Observing Story

Leading to surprising new insights about how we see plants – and fires.

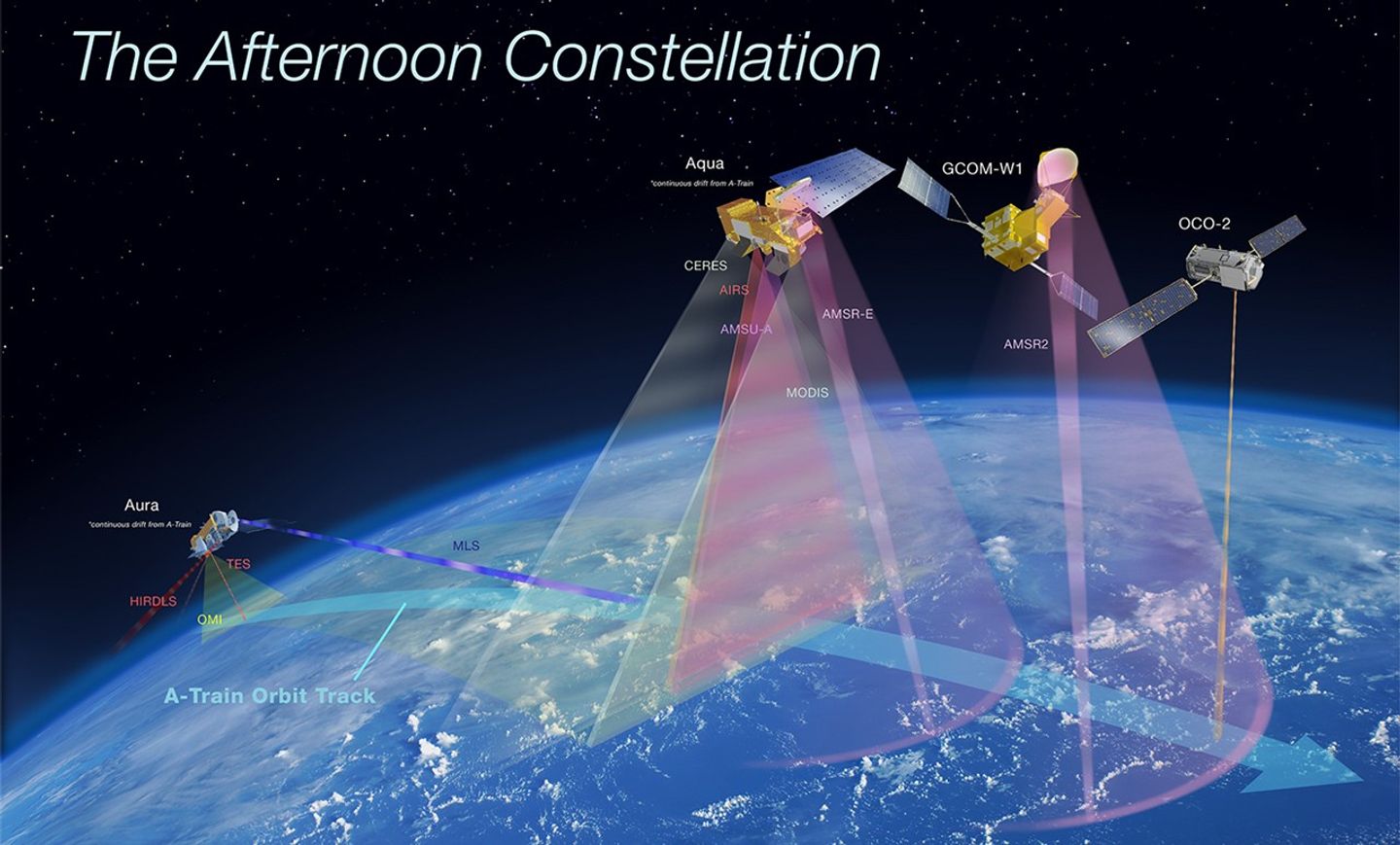

When OCO-2 launched in 2014, it joined a tightly coordinated group of Earth-observing satellites known as the Afternoon Constellation (or the “A-Train”) – see Figure 1. Flying in formation, the satellites could combine their observations to unlock more than any one mission could reveal on its own. Around the same time, scientists discovered that OCO-2 could do more than measure CO2 – it could also detect signs of plant health.

This discovery opened the possibilities for many different people, including Madeleine Festin, a former wildland firefighter in Montana, to work with OCO-2 data through an internship sponsored by the DEVELOP program, under the Earth Action element (formerly known as Applied Sciences) of NASA’s Earth Science Division.

When she was on the ground battling fires, Madeleine faced the harsh reality that fire prediction is notoriously difficult. In the field, she might be surrounded by smoke with just 20 ft (6 m) of visibility and red flames tearing through dry brush. Through her internship, she’s continued to tackle fires – just from a very different vantage point.

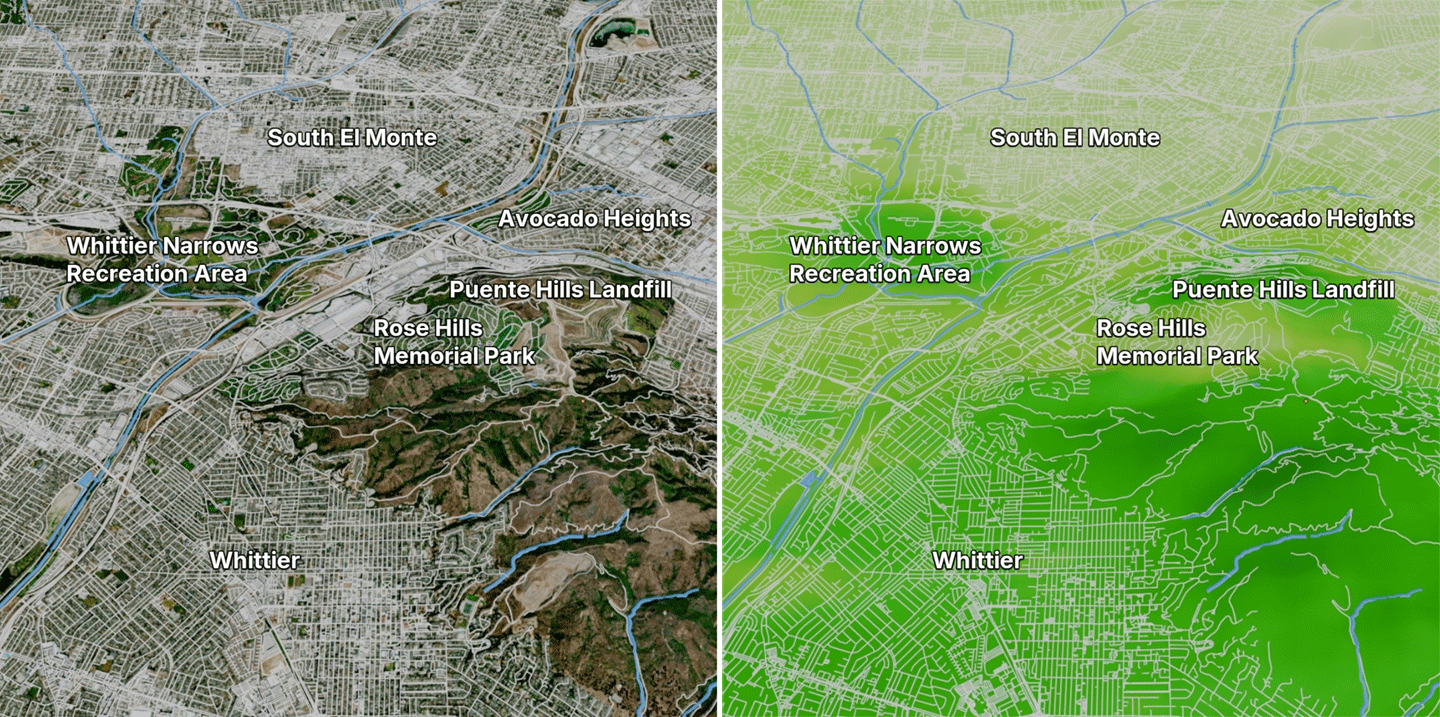

OCO-2 can detect the faint glow given off by plants during photosynthesis. This glow, called solar-induced fluorescence (SIF), offers a fast, sensitive indicator of plant health – see Figure 2. While other satellite-based tools, such as soil moisture or vegetation indices often detect stress only after damage has already occurred, SIF values drop the moment photosynthesis slows down – even if the plant still looks green. These data open the door to new applications: monitoring crop performance, identifying flood-damaged areas, and tracking drought before it sparks wildfires. That’s exactly how Madeleine is now using the data.

Madeleine’s team, a collaboration between OCO-2 scientists and the U.S. Forest Service, is working to update fire-risk models – some of which were developed in the 1980s – by incorporating SIF data.

“It’s fulfilling to know that you’re helping people,” Madeleine says. “And it’s nice to see science and firefighting work align.”

What makes the data even more powerful is OCO-2’s synergy with its A-Train counterpart, the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) instrument on NASA’S Aqua platform. MODIS contributes land-cover information that, when paired with OCO-2’s SIF measurements, creates a detailed, global dataset of plant photosynthesis far beyond what either satellite could produce on its own. This example is a perfect synergistic pairing of measurements the A-Train has made possible. This information gives Madeleine and her team a better foundation for improving fire prediction tools.

“When firefighting, I used to hear about all these fire indices and metrics, and never knew what they meant,” Madeleine says. “Now, I’m learning the science behind it. And it’s interesting to think about how to get that information to firefighters on the ground, without overburdening them. What do they really need to know, and how can we deliver it in a way that helps?”

2016: Trekking to the Desert to Calibrate OCO-2

A technologist tramps around in the desert for instrument calibration.

Carol Bruegge [OCO-2—Technologist] had been to the Nevada desert so many times that she knew the way by heart. After skirting the Sequoia Forest and stopping for the night just past the Nevada border, she led a caravan of scientists along Highway 6 to mile marker 100, turning right onto a dirt road between two fence posts. Traveling 10 mi (16.5 km) down the road, a cloud of dust raised up from the car tires before the vehicle came to a stop at their destination – a patch of spindly instruments hammered into the barren desert floor. A big plaque marked the spot with the NASA logo and the words, “Satellite Test Site.” Standing under vast blue sky, Carol felt like she’d come home. Over the past few years, Carol had grown accustomed to leading these summer expeditions to Railroad Valley, NV. Often the team from JPL is joined by guests from Japan and other international colleagues representing various satellite missions – see Photo 2.

Carol knew that a successful field campaign required that they protect the instruments from the thick corrosive salt on the ground. Then the work could begin. The team hiked through the desert, collecting data that would ensure that OCO-2 could continue to provide high-quality data. As they hiked, the team carried hand-held spectrometers and measured the reflection of sunlight off Earth’s surface – timed precisely to match the moment the satellite passes overhead. By comparing the satellite’s readings with the ground-based measurements, the team can check the accuracy of the satellite readings. Reflection is one ingredient used in calculating the concentration of CO2 in the overlying air.

This remote location in Nevada wasn’t chosen by accident. In this part of the desert, the ground is perfectly flat, free of plants, and surrounded by ground littered with salt. This smooth, bare surface means no bumps and textures could disrupt the signal. For satellite calibration, it doesn’t get better than this.

2018: A Contentious Meeting in Noordwijk, Netherlands Sparks A Revolution

Could OCO-2 data be used to construct a nation-by-nation CO2 budget?

David Crisp [JPL emeritus—original OCO Principal Investigator and former OCO Science Team Leader] was tired. He didn’t know if it was jet lag or a reflection of the 16- to 18-hour workdays that had persisted for weeks. This particular week had started with a 10-hour flight from Los Angeles to the Netherlands. Now, he was standing in front of carbon scientists who had gathered from around the world.

“We need to put together a team that will be brave enough to make a CO2 budget, nation-by-nation,” David said.

His statement was met with thoughtful silence. Neither the data nor the models were ready. The consensus in the room was that the proposed venture may not work. David was magnanimous toward his critics, but he persisted with his idea.

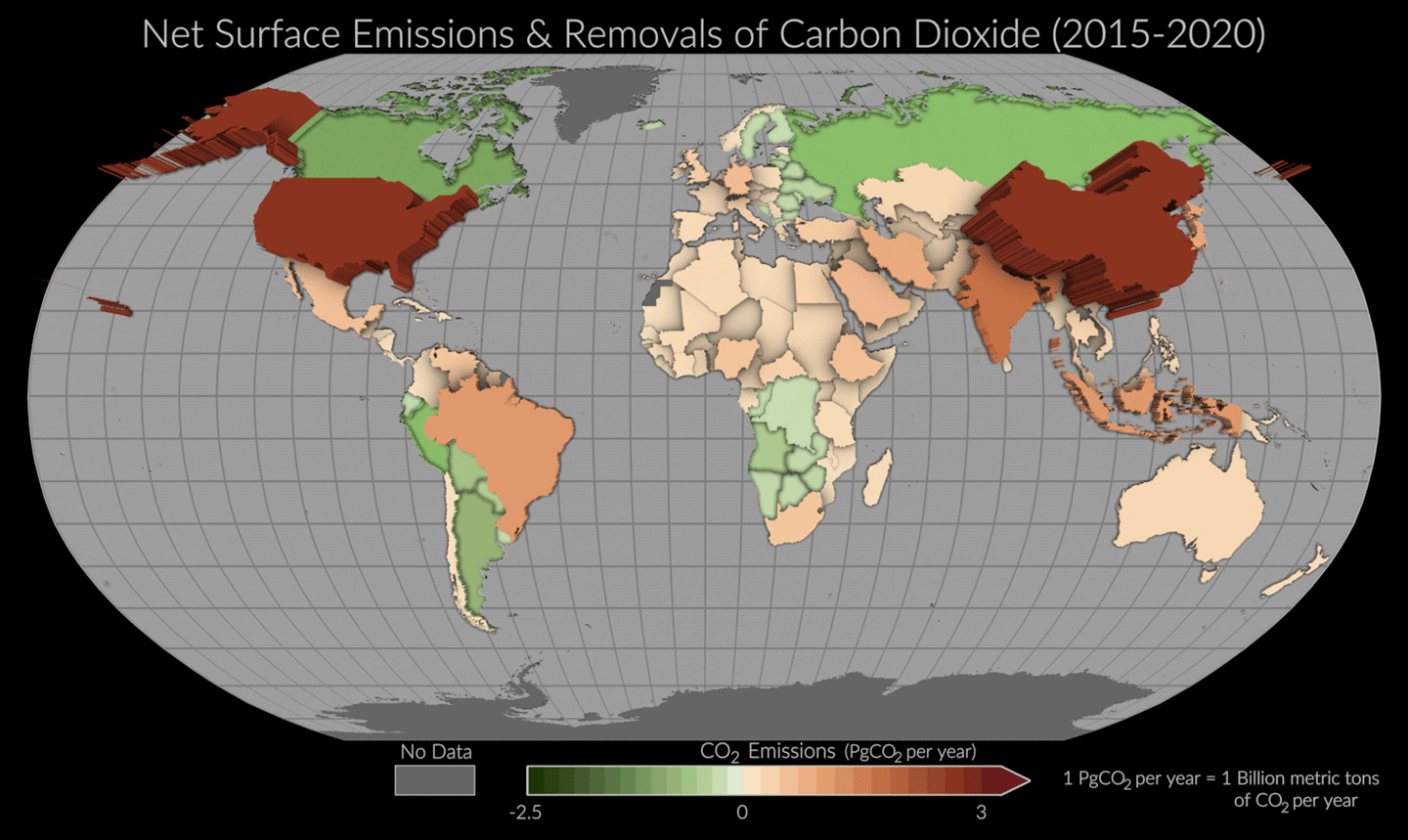

Despite the rocky start, David met with representatives in charge of creating national emission inventories. He could see exasperation on their faces – running ragged, short-staffed, and trying to tally up every single barrel of oil and bushel of coal burned within their country’s boundaries. Even more challenging was tallying other tasks, such as deforestation and agricultural practices. David firmly believed that if OCO-2 could provide independent estimates from space as promised, it would provide the on-the-ground “carbon accountants” a reliable comparison – see Figure 3.

“We might have a satellite that can help,” Dave told them.

Although David has since retired, his perseverance is now bearing fruit. What began as a hypothetical solution is now much closer to reality. OCO-2’s high-precision measurements can now detect CO2 linked not just to countries, but large cities, industrial zones, and even individual power plants – all while researchers continue perfecting efforts to identify contributions from specific city sectors. OCO-2 provides a valuable, independent reference that nations can use to track the progress of their emission inventories. Researchers have created an entire OCO-2-sourced database of CO2 estimates by country, available through the U.S. Greenhouse Gas Center.

2019: Another OCO Takes flight – This Time to The International Space Station

Using “spare parts” to get more details about plant health and the carbon cycle.

After completing OCO-2, enough spare parts remained to construct a sister mission — OCO-3, which launched in 2019 to continue the work of measuring CO2 in the atmosphere from the International Space Station (ISS). The satellite’s unique orbit gives it a new vantage point. While OCO-2 continues to orbit Earth in a near-polar path, OCO-3 travels aboard the ISS in a lower, shifting orbit that allows it to study different areas of Earth’s surface at different times of day. OCO-3 also features a special scanning mode, called the snapshot area mapping (SAM) that lets scientists zoom in on areas of interest (e.g., cities or volcanoes) to study carbon emissions and vegetation in greater detail. Together, OCO-2 and OCO-3 provide complementary perspectives on Earth’s carbon cycle and plant health at space and time resolutions that have not been possible from space before.

2021: LA During a Pandemic Is a Far Cry from Finland

A data scientist foregoes saunas and berry-picking to make the dream of OCO-2 a reality.

Otto Lamminpää [JPL—Data Scientist] opened the picture his sister had texted him. His family looked back with wide smiles, holding buckets overflowing with scarlet berries and framed by the velvety firs of Finland. It had been almost two years since he’d seen them in person. He’d moved to Los Angeles to work at JPL on the OCO-2 and OCO-3 mission just as the COVID-19 pandemic engulfed the planet – see Photo 3.

Otto had never gone a week without seeing his family or skipped a berry-hunting party in the forests of his native Finland. With the forced distance, he placed himself in his home forests in his mind. He used this memory to marvel at the capacity of the vast forests to “breathe in” CO2 and convert it into trunks, branches, and roots through photosynthesis. With the COVID-19-imposed travel restrictions, Otto wasn’t sure how long he’d have to wait to go back home.

But whenever that homecoming occurred, Otto knew that a piece of OCO-2 would be waiting for him. North of the Arctic Circle in Sodankylä, a cluster of Earth instruments nestled in a snowy meadow include a field station that is part of the Total Carbon Column Observing Network (TCCON) of Fourier Transform Spectrometers (FTS). These stations act as OCO-2 and OCO-3’s “ground crew.” As the satellites orbit Earth, the FTS simultaneously measures direct solar spectra in the near-infrared spectral region, which allows for retrieval of column-averaged CO2 concentrations, as well as other key atmospheric constituents, over the snowy meadow. Back in the lab, Otto, along with other OCO-2 and OCO-3 scientists, compare the data collected at the field station to the satellite data. This feature was detailed in The Earth Observer article, titled “Integrating Carbon from the Ground Up: TCCON Turns Ten,” was published July–August 2014, Volume 26 issue 4, pp. 13–17).

The station in Finland is one of about 30 similar TCCON sites scattered across the world, located in a variety of settings, from isolated tropical islands to the Pacific rim of Asia – see Figure 4. The stations in the far north play an especially valuable role since satellites often struggle to accurately measure CO2 over snow-covered ground. Therefore, reliable measurements from the ground stations become crucial to adjust and improve the satellite data.

Validation efforts such as the one described here are crucial to satellite observations. Comparisons between OCO-2 and TCCON show agreement is good, with a less than 1 ppm difference. It’s an impressive level of accuracy for a satellite orbiting more than 435 mi (700 km) away in polar orbit. The “ground truth” data collected at these field sites help to ensure that the satellite is accurately measuring “Earth’s breathing.”

For Otto, not just his family, but OCO-2 and OCO-3 itself was calling him home. As the pandemic began to ease, he returned to Finland to pick berries, jump in the sauna every night, and follow it up with snow angels. The homecoming was also coordinated with a trip past the Arctic Circle to the TCCON field station. The mission was part of him. Wherever he was, OCO-2 and OCO-3 would be there, too.

2023: The Annual Science Team Meeting Continues

Tracking changes in soil moisture during a colorful fall day.

Saswati Das [JPL—Postdoctoral Fellow] had missed the magnificent display of fall colors in deciduous forests of the East Coast of the United States. She’d seen nothing of the sort since moving to Los Angeles in 2022 to work on OCO-2. Before that, she’d been working on her Ph.D. at the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University (Virginia Tech), where the surrounding mountain peaks, meadows, and forests burned and sparked with crimson and gold in the autumn – see Photo 4. Now she was in another mountain town, Boulder, CO, to attend the OCO science team meeting. The aspens glittered like golden lanterns as her gang carpooled up the Flatiron Range to the science institute at Table Mesa.

The research presented that week spanned a variety of topics. OCO-2 was being used to develop early drought forecasts. Because of its ability to detect the SIF “glow” that results from plant photosynthesis, OCO-2 can hint at flash droughts as early as three months before environmental decay unfold. By pairing OCO-2 data from other satellites, such as soil moisture data from NASA’s Soil Moisture Active Passive (SMAP) mission, scientists have opened a new window into drought forecasts and how water supply affects plant growth.

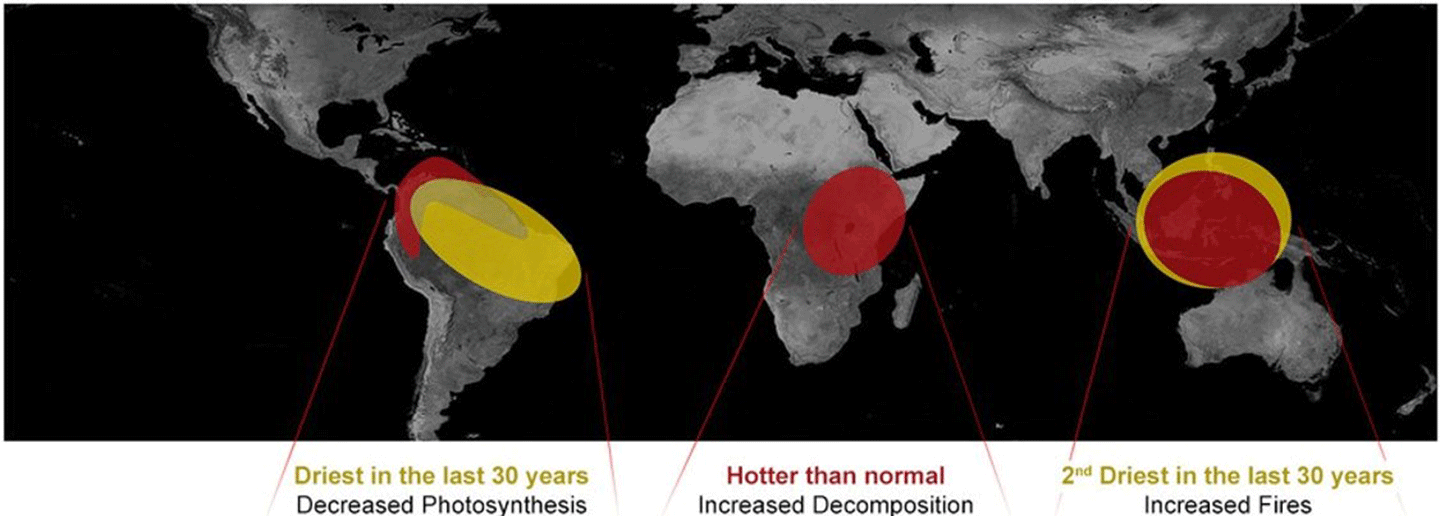

Surprises about our planet have also emerged. The tropical rainforests, long nicknamed the “lungs” of our planet, don’t always inhale and store carbon. At times, this region can exhale CO2, such as during the 2015–2016 El Niño. That period saw large tropical forests temporarily transform into net carbon sources – see Figure 5. The driver for this shift varied by region. The Amazon rainforest was driven by drought. Central Africa was driven by unusually high temperatures. Indonesia was driven by widespread fires.

Data from OCO-2 and OCO-3 have also been used to study emissions from both cities and large power plants. This approach offers a new way to track changing emissions over time – without needing to continuously measure them on the ground. In addition, scientists are combining the satellite data with wind models and urban maps to trace CO2 to its sources (e.g., factories, ships, and roadways), helping to disentangle emissions from overlapping city sectors. These methods have been used to isolate industrial emissions in places, such as Europe, China, as well as over cities, such as Los Angeles, Paris, and Seoul. It has also revealed pandemic-era drops in traffic-related CO2 and increases in CO2 tied to shipping backlogs at the port. Two representatives from the World Bank shared how they used data from OCO-2 to demonstrate that building subway systems in cities can lower emissions. The goal is to eventually use these tools to evaluate local strategies (e.g., bike lanes and public transit) to reduce local carbon footprints.

When massive wildfires blazed through Australian forests and bushland in 2019, researchers used OCO-2 data to study the unfolding crisis. OCO-2 captured the increase in atmospheric CO2, and scientists used this data to refine estimates of how these events contribute to the global carbon budget.

As her mind wandered from the rich research she’d been immersed in for the past hour, Saswati spied Otto Lamminpää across the aisle in the wood-paneled auditorium. She thought back to the forests she loved on the East Coast, and the forests in Finland where Otto had grown up. OCO-2 was telling a story about the role that forests play in absorbing carbon and how this has changed over time.

2025 and Beyond

The Tapestry Continues to Expand…

In many ways, OCO-2 has had a long and unexpected journey. So has Hannah Murphy, another DEVELOP intern who will be starting a Master’s degree at Hunter College in New York in Fall 2025. She’s studied art and worked as a set designer in Los Angeles. She never pictured herself working with satellite data, but then she saw how visual it could be. The glowing, evocative images of Earth from space spoke to her artistic heart.

Now, Hannah works on SIF data as a 2025 NASA DEVELOP intern with the OCO-2 team, developing tools for wildfire risks. This project in particular hits close to home for Hannah, because she lived through the wildfires that tore through Los Angeles in January 2025. Although she remained safe, she knew several people who lost their homes, and the air was unsafe to breathe for weeks.

Just a few short months later, Hannah began studying the data from OCO-2. She is now part of the new generation of researchers that will take the mission’s remote sensing data and pave the way for implementing the findings to benefit society. Hannah understands, on a personal level, how closely our lives are linked to Earth systems that satellites, such as OCO-2 and OCO-3, study from space.

OCO-2 (and OCO-3) are built to study CO2 and plant health, but its impact goes deeper to the connections that tie our atmosphere, ecosystems, and lives together. That work continues to the new generation of scientists – one breath at a time.

Mejs Hasan

NASA/Jet Propulsion Laboratory

mejs.hasan@jpl.nasa.gov

Alan Ward

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center/Global Science & Technology Inc.

alan.b.ward@nasa.gov